The ballad of Thor's Hammer in 19th century Jutland

The tale of the theft and recovery of Thor's hammer has proven to be remarkably popular among philologists over time. Few other Old Norse poems have been the subject of as much scholarly attention as this particular myth. The story is chiefly known from the Eddic poem Þrymskviða, but it is also attested in the late medieval Icelandic rhyme Þrymlur, as well as a substantial collection of continental Scandinavian ballads from the 1500’s and onward. An Icelandic origin mediated through Norway to Denmark and Sweden was assumed by Bugge & Moe, but according to Aurelijus Vijūnas, this model is “seriously undermined by the very numerous structural, lexical, and formulaic differences between Þrymlur and the texts from continental Scandinavia” (Vijūnas, “Problems in Mythological Reconstruction: Thor, Thrym, and the Story of the Hammer over the Course of Time”, p. 42).

The Danish material is the most complete and best attested. The earliest version is from Danish historian Anders Sørensen Vedel’s 1591 collection of ballads, Hundredevisebogen. Vedel’s version of the ballad was based on two other redactions, Svanings Haandskrift I and Bentzels Haandskrift, both of which was based on a common, now lost source. 19th century scholars were well aware of Vedel’s version when Svend Grundtvig’s collection of Danish ballads was first published in 1853 - but less than 20 years later, a living tradition was discovered on the windswept moors of Jutland.

We find ourselves on the moors of Jutland in the 19th century. The land had originally been covered by forest, but the clearing of the woods began already in prehistoric times. The last trees were felled in the Middle Ages. Then came the sand and the heather. The moor had been born, covering about a third of Jutland's area.

The moor was, first and foremost, vast. In some places it was flat, and the eye found rest on the horizon between the endless heather-covered expanses and the sky. In other places it was hilly and overgrown with scrub, dotted with twisted sand craters. Bogs and ponds caught travellers by surprise, and what few roads and paths there were came and went with the wind and weather, constanly shaped an reshaped by the feet and wheels of travelers.

The scattered settlements on the moors were small and primitive, and in some places people eked out a living at the edge of existence. But the ordinary and poor folk often possessed a wealth that was now rapidly disappearing: a rich folkloric tradition.

In the 1800s, researchers and cultural figures had begun to take an interest in folklore, and started collecting old stories, folk songs and accounts of daily life. But it was a race against time: traditional rural life was rapidly disappearing. The old people were dying, and their stories with them, and younger generations didn't attach the same importance to folklore as previous generations.

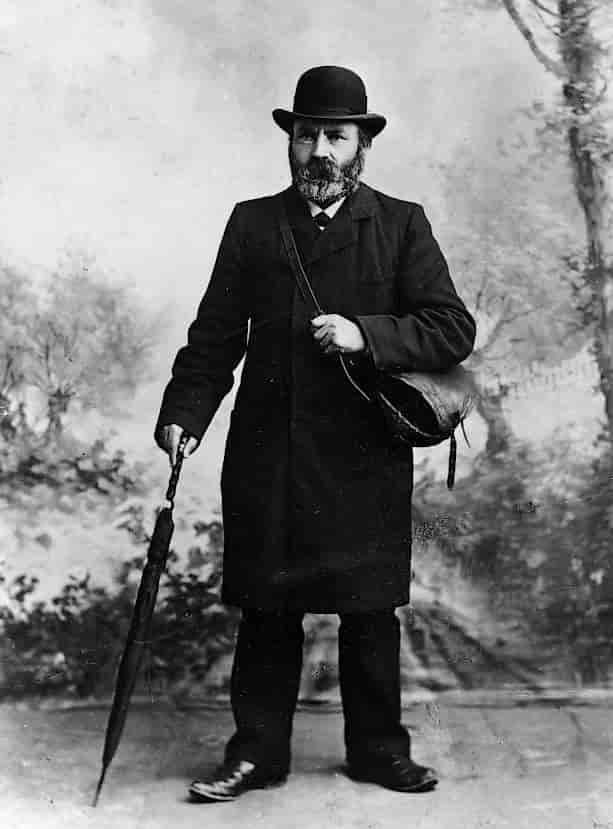

One man in particular came to play a monumental role in the documentation of Danish folklore and folk life: Evald Tang Kristensen.

The Collector

Born in 1843, Kristensen became one of the greatest and most prolific folklore collectors of all time. He collected examples of virtually every genre of folklore, provided data on his informants, and took down texts verbatim in their local dialect. From 6500 informants, more than half of which he personally sought out, he recorded some 3000 songs and ballads, a thousand melodies, 2700 fairy tales, 2500 jokes, 25000 legends, numerous sayings, poems and riddles as well as thousands of descriptions of traditions and everyday life. Kristensen criss-crossed the Jutlandic peninsula, making over 260 field trips and traveling over 70,000 kilometers, most by foot. His work has been published in almost eighty volumes.

Kristensen's interest in collecting folklore was born from tragedy. He graduated as a school teacher in 1861, spending a few years as assistant teacher in Northern Jutland. In 1866, Kristensen became a teacher in Gjellerup, east of Herning. He married his first wife, Frederikke, in the same year. However, amidst the joy of their new family life, tragedy struck when Frederikke died in labor, along with their child. The loss of his new family was a hard blow for the 23-year-old Kristensen, but it also became the starting point for his work as a folklore collector.

In 1884, Kristensen began writing an unpublished autobiography in which he wrote:

"I brought my bride home the same spring as I came to Gjellerup, but she died in the autumn. In my loneliness, it was as if the Lord would grant me diversion with the collection of folk memories. During the daytime, I taught at school, and in the evenings, I went hunting [for information]".

Throughout his life, Kristensen would work closely with prominent Danish scholars such as Svend Grundtvig, Axel Olrik and Henning Frederik Feilberg. Men whose work took place at their own desks. The collaboration was not always without problems, as Kristensen belonged to a lower social class than the professors. In a letter to Hans Ellekilde, Kristensen wrote about Feilberg that:

"[He] was an academic, and basically looked down on all non-academics, i.e. unlearned people, and all such petty people were really only nobodies, if they could not serve his purpose. But, by the way, this is the same way of thinking you constantly encounter in all academics, for they belong to the upper class".

According to Kristensen, Grundtvig could also behave in a patronising manner, something that was certainly not to his liking. Kristensen saw himself as more akin to his informants, despite being higher up the social ladder than them. Kristensen occupied a medial position, balancing as a link between the learned academics above him and the informants below him.

Unlike his academic superiors, he expressed a deep admiration for his informants. In 1898, he wrote in an article that:

They are all bearers of our old traditional spiritual life. They are the finest among the population, gifted with excellent mental faculties, a lively interest in everything great and noble, and a good understanding of the importance of human life. I have used the expression "doubtful existences" above, but these are not my own words; quite the contrary, as I do not regard these people as unreliable. The word is used by people who overlook them because those who are not on the shadow side of life look at others with eyes that are anything but understanding. The smug and boastful must absolutely believe themselves to be smarter than the quiet and humble. I only wish that many could have shared the joy I experienced in getting to know so many of these bearers of our old cultural life, and in sitting and listening to them with an understanding of what they have brought forth from their rich storehouse. It would certainly form a good counterbalance to all the vapidity of today.

Now, this old nobility of spirit is soon to be extinct. There is a peculiar poetic flavour to this whole series of pictures I have in front of me. What is inherited from the ancestors, they have passed on with all possible fidelity to the next generation, delighting in the poetic images they brought with them, and delighting others with themselves. Yet, these people are but the last manning the ramparts. They were preceded by others who were even more skilful and had much more to offer. From my own time, I remember with joyful sadness Jens Povlsen in Tvermose, who has told me a total of 53 fairytales; Niels Pedersen in Mejrup; Niels Kristian Jensen in Fredbjærg; Peder Frølund in Skibild; Frands Povlsen in Grødde; Ane Johanne Andersdatter in Mammen; Ane Povlsdatter in Tvermose; Ane Jensdatter in Rind; Kristence Kristensdatter in Hygum; Niels Kragelund in Hølund; Bodil Kristensdatter in Grødde and many many more.

They are all dead.

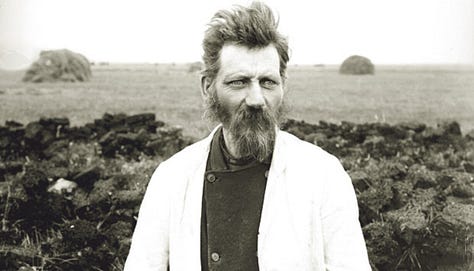

The Informants

Kristensen encountered the ballad of Thor a total of 4 times. The first person to sing the ballad of Thor to Kristensen was the renowned ballad singer Iver Pedersen in the summer of 1869. At the time of Kristensen's visit, Iver was an old man in his seventies (sources differ on his exact age), living with his son, his daughter-in-law, and their four children. Kristensen describes Iver as tall, upright and powerfully built man who moved around easily and spoke quickly. Known for his good and social nature, he was very willing to sing his ballads and tell his stories to Kristensen. Iver sang no less than 17 ballads for Kristensen and knew how to deliver a performance that could captivate the audience and make them burst into laughter.

Kristensen describes Iver's performance as follows: “He was the first to sing the ballad of Thor to me, and he performed it with such vigor and liveliness that it was as if you could see Thor standing in front of you”.

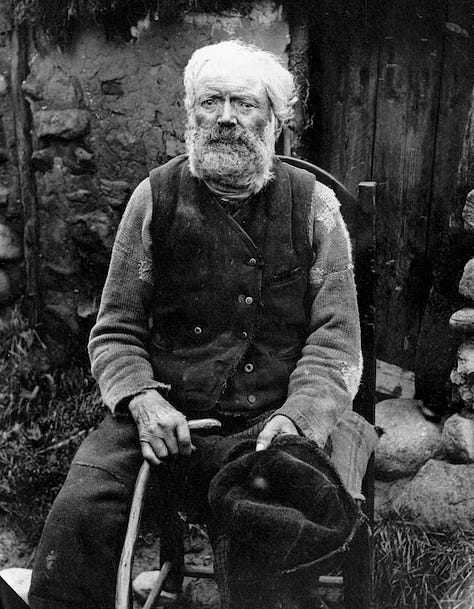

The next two informants were brother and sister: Ane Poulsdatter, born in 1816, and Peter Poulsen, born in 1811. Ane lived with Peter, his wife Karen, their three children, and the men and women working on their farm. According to Kristensen, Ane appeared “small and inconspicuous, but she had very developed mental abilities".

Like his sister, Peter was also well-versed in ballads, and the whole family, with their highly developed poetic sense and great skill at performing, made a lasting impression on Kristensen. He recorded the ballad of Thor from Ane in 1872 and from Peter in 1874. The family lived about 8 kilometers from Kristensen's home, and the journey there made for a perilous crossing across the moor. Here, Kristensen describes one such trip in 1872:

It was winter, or rather late autumn when I walked over to Tværmose, a mile from my home, but the distance between the two places was exceptionally impassable. It was a very rainy autumn, and all the meadows were flooded. From Lund school, where I taught until evening, I could find the road to Sønderbjærg, but from there, there was hardly any road or path, only the black moor. After crossing it, I came to a stretch of wetland full of water, which I had to wade through, only navigating by the odd tuft here and there that I had noticed.

Next came another stretch of moorland, just as rough as the previous one, and then a bog with a stream that I had to jump over, which could be difficult enough as it was overflowing. Once past the water in the meadow, I was able to get myself up on the bank of an upturned ditch, but I had to walk very carefully to avoid falling into the water. After crossing yet another dark moor, at last came the wide meadow along Storåen, which was like a large lake, for the water had been dammed up, and the ditches were overflowing with water.

I then had to cross three ditches almost at the risk of my life, and then came the very swollen river, where I had to cross a rough beam that formed the upper edge of the dam. The opposite ditch was not so bad to cross, but I had to be very careful not to take a wrong turn and plunge into one of the hidden ditches. Here, too, everything was like a lake, with no visible mark other than some scattered tufts and a few remnants of ditch banks that had not yet been flooded.

That was now the outward journey. The return journey was, if possible, even more dangerous. It was nearly midnight, and if I had fallen in, my cries could not have brought anyone to my rescue, as people had gone to bed, and I was traveling on a stretch of road very far away from inhabited places. Across the moors, I had nothing to look to but the stars and the distant light in Gjellerup, almost 6 kilometers away, a farm where people went to bed very late.

It was nothing short of a miracle that I came back from these trips alive.”

And finally, Kristensen recorded one single verse from Ane Marie Pedersdatter in Grimstrup, in 1872.

These versions were treated and synthesised by Grundtvig in the fourth volume of Danmarks Gamle Folkeviser, pp. 580-582. Here follows the translation:

Thor of Haagensgaard

1 It was Thor of Haagensgard,

and he rode across the meadows:

there he threw away his hammer of gold,

and gone was it for so long.This year, Sweden will be won.

2 It was Lokki Læjermand,

he put on his coat of feathers:

then he sailed to Norway-Fell

across seas and salty water.3 It was Lokki Læjermand,

he steered his ship to land:

and it was the good thurs count,

he strolled down to the strand.4 "Welcome, Lokki Læjermand!

and be welcome here!

How fares Thor of Haagensgard,

what is the lay of the land?"5 "Well lives Thor of Haagensgard,

he sits at home with honour:

Last year he lost his hammer of gold,

that is why I have come here."6 "Your hammer is found,

you can not have it:

for it lies full four

and fourty fathoms into the ground."7 "Your hammer is found,

you can not win it:

before we get your sister,

a paragon of all women".8 It was Lokki Læjermand,

he put on his coat of feathers:

then he sailed back again,

across seas and salty water.9 It was Lokki Læjermand,

he steered his ship to land:

and it was Thor of Haagensgard,

he strolled down to the strand.10 "Our hammer is found,

we can not have it:

for it lies full four

and fourty fathoms into the ground."11 "Our hammer is found,

we can not win it:

before they get our sister,

a paragon of all women."12 Up stood their old grandfather,

he was thin like a reed at the waist:

"And I shall be the young bride,

if you will take me there".13 Then they took their old grandfather,

shaved off his beard and hair:

then they took him to Norway-Fell

as a maiden fair.14 Then silk and white sendal

was spread on the black ground:

and then the good young bride

was led up to the castle with honour.15 "Welcome, Lokki Læjermand!

Welcome to our home!

But first of all the young bride,

who is so fair a maiden!"16 Yea, twelve were the champions

who brought the bride to her seat:

and twelve were the champions

who began to pour for the bride.17 She ate up seven oxen,

and some fat sheep,

seven sides of bacon on top of that,

she was so fair a maiden.18 Yea, it was the good, young bride,

and she began to drink:

she emptied out a keg,

and began to hiccup.19 Then entered the thurs count,

he shone so red of gold.

"What an odd bride you must be,

that you can not get drunk!"20 "Whether I eat little, or I eat much,

never will I get enough:

before I have eaten my bridal porridge,

cooked in a seven-barrel pot".21 "Whether I eat little, or I eat much,

never will I be sated:

before I get to see my brother's hammer,

that has been lost for so long."22 Twelve were the champions

who dug up the hammer from the ground:

but eighteen were the champions,

who carried the hammer to the table.23 Eighteen were the champions

who carried the hammer to the table,

but it was the good, young bride,

she lifted it with two fingers.24 Yea, it was the good, young bride,

and she began to whip:

then she slew all the champions

with her snare tip.25 It was the good, young bride,

she sprang so easily across the table:

she brought down eighteen panels along with her,

then she went home to Thor.This year, Sweden will be won.

And that must suffice for now. If you are interested in learning more, I recommend peering through Vijūnas’ paper, freely available here. This will not be the last I make a folkloric digression :-)

Literature:

Svend Grundtvig - Danmarks Gamle Folkeviser, vol. I (1853) & vol. IV, (1883).

Evald Tang Kristensen - Jydske Folkeviser og Toner, 1871.

Evald Tang Kristensen: “Visesangere og Eventyrfortællere i Jylland” in: Illustreret Tidende. vol. 40, nr. 3, 1898.

Evald Tang Kristensen - Minder og Oplevelser, vol. 2, 1924