The Lay of Helga

Translation and commentary

The so-called Lay of Helga is preserved only Danish medieval literature’s greatest work, Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus, written around 1208. Saxo knew how to flex his literary muscles: he wrote his history of Denmark in florid Silver Age Latin, and in the first eight books, the reader also encounters poems written in no fewer than 24 different classical metres. Saxo claims that the poems are translations from Old Norse verse. There is no reason to doubt this, but at the same time, it is clear that the translations bear the mark of Saxo’s own aims and methods. This is also true of the Lay of Helga, which is a satire modeled after Juvenal and Horace. This is further emphasized by Saxo’s associative borrowings from these very poets.

The dating of the lay’s Old Norse original is disputed. There is general agreement that the Lay of Helga was inspired by the Lay of Ingiald. Based on references to clothing, social status, and literary trends, scholars have proposed dates ranging from the reign of Harald Bluetooth to well into the 12th century. Much points to a late dating.

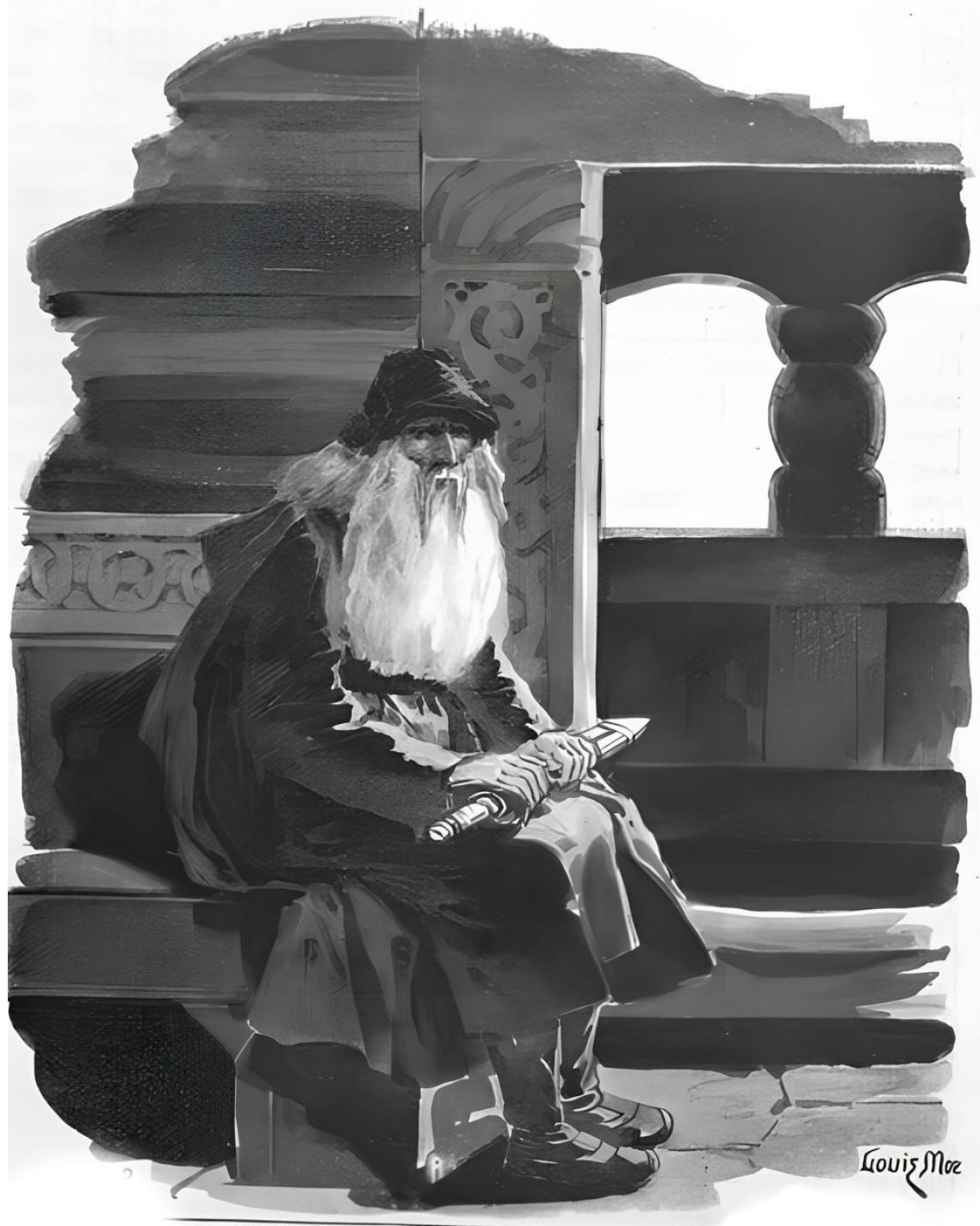

The speaker of the poem is Starcather, a legendary Scandinavian hero known for his strength and resolve, but also for the three nithing-deeds he committed at the behest of the gods, most notably the killing of king Víkarr. According to Old Norse tradition, Starkaðr was one of the earliest known skalds, particularly renowned for composing verses about the kings of Denmark. In the 12th century, there was a strong interest in Denmark’s ancient past in Iceland and the Orkney Islands, and many works from this period revolve around Danish themes, including Starkaðr. Saxo thus had a wealth of material to draw upon, possibly mediated to him by the exiled Norwegian clergy and their entourage.

In Gesta Danorum, Starcather is a representative of aristocratic values and an austere warrior ethos perceived to be under threat from the powerful, courtly cultural influences coming especially from Germany. In this way, Starcather served a mouthpiece for Saxo’s own critique of contemporary society, much of which he appears to have considered degenerate.

The story so far:

Princess Helga had been seduced by an ignoble goldsmith. After the death of king Frothe, she was left without a guardian, and no one was there to protect her honor. When Starcather heard travelers tell the story, he was outraged by the goldsmith’s audacity and resolved to repay king Frothe’s past kindness by taking revenge on the smith.

Starcather immediately traveled to the goldsmith’s house and seated himself just inside the door, with his hat pulled low to avoid being recognized. The smith, not learned enough to know that heroic hands sometimes lie beneath a tattered cloak, mocked him and shouted that he should go outside. There, he’d be given scraps with the other beggars. Starcather, however, remained seated, observing the smith’s behaviour.

The smith lay in Helga’s lap, asked her to comb his hair and groom his groin. He even groped her breasts. But when Helga caught sight of Starcather in the corner, she became so embarrassed that she pushed the smith’s hands away and told him that what he needed now was a weapon.

At that point, Starcather could no longer restrain himself. He threw aside his cloak and drew his sword. The goldsmith made no attempt to resist but tried to flee. Just as he reached the threshold, Starcather struck him in the buttocks, so he collapsed half-dead. When Starcather saw how dismayed the household was over their master’s misfortune, he mocked the wounded man further with these words:

Translation and commentary:

1.

Why is the house struck dumb with speechlessness?

What is the cause of this renewed sorrow,

and where is that charmer of women resting,

whom I recently punished with my sword for his depraved desire?

Surely he hasn’t still kept his arrogance and idle luxury,

clinging to his pursuits and seething with nascent lust?

He must bide his time and trade words with me,

and amend yesterday’s enmity with friendly speech. [1]

Lift a happier face, let not lament echo through the hall,

nor the expressions freeze into sorrow.

[1] The smith is indisposed and does not respond.

2.

I wished to discover who was aflame with passion for the maiden,

who was overcome by burning love for my foster daughter.

I pulled my hood down so as not to reveal my features,

as the shameless smith entered with lewd steps,

wriggling his hips from side to side with practiced gestures,

no less skilled in nodding and casting glances at everyone.

The cloak around him was trimmed with beaver fur borders, [2] [3]

his shoes studded with precious stones, his tunic adorned with gold. [4]

A sparkling band bound his braided locks,

a variegated and fluttering ribbon fastened his hair. [5]

This inflated his cowardly mind and arrogant thoughts,

he confused wealth with lineage, money with ancestry,

counting goods and gold as better than blood.

Thus pride rose, and vanity overcame the spirit.

Such appearance led the wretch to fancy himself a nobleman,

a highborn’s equal, that ash-blower, who captures gusts in hides [6]

and, by steady drawing, produces puffs of air,

raking fingers through ashes, pulling again and again at the bellows

to catch the air, and blowing through the narrow mouthpiece

to awaken the sluggish flames.

[2] Saxo describes the smith’s clothing with borrowings from Virgil’s depiction of Dido in the Aeneid. Just as Dido’s love threatens Aeneas’ mission, the smith’s desire threatens Helga’s virtue. This borrowing also implies that his outfit and ostentatious appearance are effeminate.

[3] There is archaeological evidence of garments made from beaver fur. Use of beaver fur in clothing and trade in beaver pelts is also documented by Adam of Bremen and in saga literature.

[4] The smith’s attire closely resembles Charlemagne’s ceremonial dress as described in Einhard’s Vita Karoli Magni, where he “went about clad in a gold-embroidered robe and shoes set with precious stones.” Golden shoes are also mentioned in Saga Óláfs konungs kyrra.

[5] According to Einhard, Charlemagne also wore “a diadem of gold and precious stones.” Headbands are depicted in Carolingian art, such as in the Bible of Charles the Bald. Similar items are known in Old Norse literature as ennidúkr, gullhlað, silkihlað, and gulld lad in Danish ballads. Starcather also inveighs against headbands in the lay of Ingiald.

[6] Ash-blower (Latin: ciniflo) is a Horatian term used pejoratively for the smith’s work. Tending the fire and raking through the ashes was a menial task reserved for the lowest member of the household. Elsewhere in Gesta Danorum it is referred to as thrall’s labour. From saga literature, we know the kolbítr (“coal-biter”); in Danish folk tales, the askefis (“ash blower”). The dirty and worthless layabout is the antithesis of the active hero. Incidentally, Starcather himself also began his career as a sluggard, cf. Víkarsbálkr 5.

3.

Next, he sought the maiden’s lap and lay there:

“Maiden,” he said, “comb my hair and squeeze the leaping fleas [7]

between your nails, remove what stings my skin!” [8]

Lying back, he stretched out his gold-adorned and sweaty arms, [9]

reclining on a soft pillow, supporting himself on his elbow

to show off his finery, like a barking beast [10]

that stretches and waves the curved bows of its tail. [11]

She recognized me and tried to restrain her suitor,

lifting his grasping hands and said that I was present:

“I beg you, move your fingers,” she said, “and control your excitement,

try to appease the old man by the door.

Wantonness can end in regret. I believe Starcather is here,

watching your actions with a lingering eye.” [12]

To this, the smith replied: “Do not turn pale on account of a harmless raven,

a tattered old man: the mighty champion you fear [13]

would never endure such filthy rags.

Great warriors take pleasure in wearing fine garments,

and a warrior’s spirit demands fitting tunics.” [14]

[7] Leaping fleas. The adjective salāx strictly means “prone to leaping” but is always used in a sexual context; salacious, lustful, eager, etc. including by Horace.

[8] Stings (Latin: uritur). The verb uro does not only mean to burn, sting, but also to burn with love or lust.

[9] The gold-adorned and sweaty arms are borrowed from Juvenal’s First Satire, where he skewers the effeminate, nouveau riche, foreign upstarts in Rome. In other words, exactly the same type of person as the goldsmith in the Lay of Helga.

[10] Barking beast (Latin: belua latrans). Belua means wild animal, beast or monster, and Saxo otherwise uses this word only for wild animals, dragons, giant bears, and the like. The participle leaves no doubt, however, that what is intended really is a dog. It was a grave insult to call another man a grey or bikkja (“bitch”). Laws such as the Gulaþing Law classify this as fullréttisorð, i.e., words that demanded full compensation.

[11] Tail, (Latin: cauda). The word means tail, but is also used for the penis in Horace’s satires.

[12] Starcather displays the classical virtue temperantia, moderation and self-control. The smith does the exact opposite, giving in to luxuria and libido.

[13] Unlike in other poems about Starcather, his reputation precedes him here.

[14] Cf. the proverb Hwer er saa hædh som han ær klædh, literally “every man is as honoured as he is dressed”.

4.

Then I cast off the disguise,

drew my blade, and cut off the fleeing smith’s genitals, [15]

exposing how the testicles hung severed from the bones, displaying the entrails. [16]

Immediately I sprang up and struck a fist into the maiden’s mouth,

beat the blood from her nose. Then the lips, accustomed to wicked laughter, [17]

were soaked with the mingled flow of blood and tears,

and foolish lust was castigated,

for all that seductive glances had transgressed against.

Ill she has played, who, blinded by desire, lets herself

be lead like a mare in heat, and burns her honour on the pyre for the sake of lechery. [18]

You deserve to be sold to foreign peoples, worthy of the millstone, [19] [20]

unless blood squeezed from your breasts

proves the accusation false,

and lack of milk rejects the charge. [21]

Yet I consider you innocent in this matter,

but beware of arousing suspicion,

or exposing yourself to false tongues,

and letting the vile gossip of the mob tear you asunder. [22]

Rumors harm many, and deceitful gossip has caused damage. [23]

A small word can mislead the common perception.

Honor your ancestors, respect your lineage, remember your family, [24]

and keep your kin in mind: let your heritage maintain its honour.

[15] The smith does not possess an ounce of fortitudo, manly courage, and flees the moment Starcather draws his blade. He should have heeded Helga’s advice in the previous stanza. A similar scenario occurs later in the book: Starcather is angry at Helga’s husband, Helge, because Starcather had to fight alone. Helga knows Starcather is returning to avenge what he sees as Helge’s cowardice and lechery. She advises Helge to strike Starcather as soon as he enters, because he had a habit of sparing the bold and punishing the cowardly. Helge follows this advice, and all ends well.

[16] This is what laws like Grágás classifies as a klamhǫgg. The severing of another man’s genitals was considered equivalent to murder in medieval laws. As Anders Sunesen explains in his Latin paraphrase of the Scanian Law, “many men would choose death rather than live a shameful life after losing their genitals”. A klamhǫgg is also a physical manifestation of níð, charged with symbolic sexual violence that deprives the mutilated man of his manhood.

[17] The blow to the nose might be seen as a milder form of nasal amputation, which was a common punishment for adultery in Europe. Elsewhere in Gesta Danorum, Hialti cuts off his mistress’s nose over a question he finds too lewd and disgraceful.

[18] In both classical and Old Norse literature, lustful women could be compared to mares. This insulting mockery could be done not only with words but also by neighing at women, as happened to Sigríðr stórráða later in Gesta Danorum. Men could also be compared to mares, which required full compensation, cf. note 10.

[19] Sold to foreign peoples. Adam of Bremen reports around 1075 that this was how unfaithful women were punished in Denmark. The ballads Hillelilles Sorg (DgF 83) and Jomfruens Straf (DgF 464) may echo this custom.

[20] Worthy of the millstone. Working at the mill was hard physical labour. Elsewhere in Gesta Danorum, it is work for thrall women. Compare also with Fenja and Menja in Gróttasǫngr.

[21] A primitive test of virginity.

[22] The Latin original

Carpendam […] loquaci

Rumor…

is found again in the Lay of Ingiald as

Carpor […] loquaci

[…] rumor

and constitutes yet another parallel between the two poems.

[23] A loan from Horace’s Epistles. Both passages deal with the harm that lies can cause. It was therefore natural for Saxo to borrow from there, although the meaning may be deeper. A few lines further down in the epistle, Horace writes:

Yet the whole household and the entire neighbourhood

see this man as ugly inside, though fair in appearance.

It is tempting to read this alongside the prose introduction to the Lay of Helga: “The smith, not learned enough to know that heroic hands sometimes lie beneath a tattered cloak”. This is also known as a later Icelandic proverb: Opt er vösk hönd undir vondri kápu. The smith is therefore too stupid to recognize a proverb when he sees one. He’s the type of man who would cross a river to fetch water. The loan from Horace, combined with this description of Starcather, presents a contrast between the two: Starcather is poor in appearance but possesses the right virtues, whereas the smith is fair in appearance but full of vices.

[24] Ancestors, lineage, family, kin: Saxo reveled in varied expressions, much to the regret of translators.

5.

What madness struck you? Shameless smith, what fate [25]

drove you to tempt your lust upon a noble daughter?

And who led you, a maiden worthy of a famed bed,

to lowborn love? Tell me, how could you dare

to taste a soot-stained mouth with your rosy lips, [26]

endure the coal-darkened hands on your breast,

lay the coal-stained arms around your waist,

let hands hardened by the toil of the tongs

stroke your honourable cheeks, and take the ember-spattered head

and clasp it tightly in the shining embrace of your arms? [27] [28]

[25] Madness (Latin: furor). See note 26 below.

[26] Rosy lips (Latin: roseis labellis). All commenters agree that this phrase does not seem ancient. So where does it come from? One possibility is that, ironically, despite Saxo’s criticism of German customs, the phrase comes from German minnesänger. These were court poets and troubadours active from the 1100s to 1300s, also present in Denmark during Saxo’s time. Saxo himself reports that one minnesänger tried to warn Knud Lavard against Magnus’s betrayal, by singing about Kriemhield’s treachery. Heinrich von Morungen, a key minnesänger around 1190–1200 (right when Saxo wrote), used phrases like rôsevarwer rôter munt (“rose-coloured red mouth”) and rôsevarwen munde (“rose-coloured mouth”) in songs about beautiful women. This imagery also appears in Gottfried von Strassburg’s Tristan (rôsevarwer munt) and the Nibelungenlied (rôsenvarwer munt).

Another possibility is that Saxo’s rosy lips stems from a classical source. We find roseis labellis in Catullus’ Carmen 63. Them poem is about Attis, a beautiful young Greek seized by madness (Latin: furor). He sails to Prygia and dedicates himself to the goddess Cybele, whose priests are eunuchs. Attis castrates himself and flees to a mountain sacred to Cybele. The next day, as his madness fades, he delivers a repentant speech, his rosy lips uttering the words. This parallels Saxo’s themes of madness, castration, and rosy lips. However, Catullus’ poetry seems to have been very rare in the Middle Ages. One of his poems is preserved in an 800s florilegium, bishop Raterius of Verona mentions him in a sermon, and a manuscript containing his poems also existed in Verona in the 1200s. This manuscript later disappeared, but only after being copied and preserved in three manuscripts from the 1300s.

[27] The shining embrace of your arms. Skaldic poetry often praise women as pale, white-armed, white-browed, etc. Saxo’s version of Bjarkamál likewise depicts women with snow-white shoulders.

[28] The contrast between the soot-covered smith and the white, rosy-lipped maiden underscores the social gulf between them, making their love not only impossible but disgraceful. Saxo revisits this theme repeatedly in Gesta Danorum.

6.

I recall how great the difference is among smiths;

they once beat me. Though the name is shared, [29]

and each man shares the same craft,

beating hearts differ beneath their chests.

I hold in highest regard those who forge swords and spears for warriors’ strife,

who reveal their spirit through their craft,

display their temper through the toil of their trade,

and make known their boldness in the work.

But there are others who melt ore in the hollow of the crucible, [30]

let the molten gold mimic every shape,

heat up the metal and smelt down alloys, these possess a softer mind and soul.

Hands gifted with skill are also stricken with fear. [31]

Such men often deceive. When the bellows fan the flames

and ore is poured into the crucible, they secretly steal crumbs [32]

from the golden mass, while the vessel thirsts for the pilfered metal.

[29] They once beat me. This episode is also referred to in Starcather’s Death Song. During a campaign in Telemark, Starcather was beaten by smiths with their hammers.

[30] The hollow of the crucible (Latin: caua testula). A borrowing from Prudentius’ Cathemerinon.

[31] That weaponsmiths possess manly courage is something Starcather has learned firsthand, cf. note 29. He has now also had it confirmed that goldsmiths lack manly courage, cf. note 15.

[32] Yet another addition to the goldsmith’s extensive catalogue of vices: he is also thievish. As if that weren’t enough, he steals in the manner of a thrall. He pilfers crustulae, just like slaves do, cf. Juvenal’s Ninth Satire: nos colaphum incutimus lambenti crustula seruo, "we deal a blow with our fist the slave who licks the treats." This too is a double entrendre.

Secondary literature:

James Noel Adams, The Latin Sexual Vocabulary, 1982.

Barry Baldwin, "Juvenal's Crispinus", in: Acta Classica, Vol. 22, 1979, p. 109-114

Luise Ørsted Brandt et al., "Palaeoproteomics identifies beaver fur in Danish high-status Viking Age burials - direct evidence of fur trade", in: PLoS One, vol. 17., 7, 2022.

Karsten Friis-Jensen, Saxo Grammaticus as Latin Poet. Studies in the verse passages of the Gesta Danorum, 1987.

Bjarni Guðnason, “The Icelandic Sources of Saxo Grammaticus” in: Karsten Friis-Jensen (ed.), Saxo Grammaticus. A Medieval Author Between Norse and Latin Culture, p. 79-95.

Birgit Herbers & Kristin Rheinwald, "und ir rôsevarwer ròter munt... der was sô minneclîch gevar. Über konkrete und unkonkrete Farbbezeichungen mit -var im Mittelhochdeutschen", in: Farbe im Mittelalter. Materialität - Medialität - Semantik, band II, 2011, p. 419-439.

Paul Herrmann, Erläuterung zu den ersten neun Büchern der dänischen Geschichte des Saxo Grammaticus von Paul Herrmann. Zweiter Teil: Kommentar, 1922.

Kurt Johannesson, Komposition och världsbild i Gesta Danorum, 1978.

Gottfrid Kallstenius, "Nordiska ordspråk hos Saxo" in: Studier til Axel Kock, ANF (Tillagsband til bd. 40), 1929, p. 16-31.

Axel Kock, Östnordiska och latinska medeltidsordspråk, II, 1892.

Sigurd Kværndrup, Tolv principper hos Saxo. En tolkning af Danernes Bedrifter, 1999.

Anker Teilgård Laugesen, Introduktion til Saxo, 1972.

Alina Laura de Luca, "«Catullum Numquam Antea Lectum […] Lego »: A Short Analysis of Catullus’ Fortune in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries", in: International Exchange in the Early Modern Book World, Matthew McLean & Sara Barker (eds.), 2016, p. 329-342.

Kemp Malone, "Primitivism in Saxo Grammaticus", in: Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1958, p. 94-104.

André Muceniecks, Saxo Grammaticus. Hierocratical conceptions and Danish hegemony in the thirteenth century, 2017.

Guðrún Nordal, Tools of Literacy. The Role of Skaldic Verse in Icelandic Textual Culture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, 2001.

Axel Olrik, Danmarks Heltedigtning II - Starkad den Gamle og den Yngre Skjoldungerække, 1910.

Erik Petersen, "Om kilderne til kilderne. Birger Munk Olsen og studiet af de latinske klassikere indtil år 1200" in Fund og forskning i det kongelige biblioteks samlinger, bind 54, 2015, p. 167-182.

Russell Poole, "Some Southern Perspectives on Starcatherus" in: Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, Vol. 2, 2006, p. 141-166.

Wilhelm Ranisch, "Die Dichtung von Starkað", in: Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur, 72. Bd., H. 3, 1935, p. 113-128.

Herrmann Schneider, Germanische Heldensage. II. Band, I. Abteilung: Nordgermanische Heldensage, 1933.

Patricia Skinner, "The Gendered Nose and its Lack: “Medieval” Nose-Cutting and its Modern Manifestations" in: Journal of Women's History, vol. 26, 1., 2014, p. 45-67.

Patricia Skinner, Living with disfigurement in early medieval Europe, 2016.

Inge Skovgaard-Petersen, Da Tidernes Herre var nær, 1987.

Preben Meulengracht Sørensen, The unmanly man. Concepts of sexual defamation in early Northern society, 1983.

Weiss, Hermann: Kostümkunde. 2,2, Geschichte der Tracht und des Geräthes im Mittelalter vom 4ten bis zum 14ten Jahrhundert ; Das Kostüm der Völker von Europa, 1864.

Very interesting post. I was not aware of this work.

Just one critique: “…from the powerful, courtly cultural influences coming especially from Germany.”

There will not be a Germany until 1870 and nothing resembling a German identity until 1500, even then its about a language group. There are a plethora of German speaking principalities.

I use the phrase “German speaking regions” in the Middle Ages, but even then, which dialect? Low or High German?

There are English and French identities in the Middle Ages, but medieval German speaking ppl are way behind in this regard.