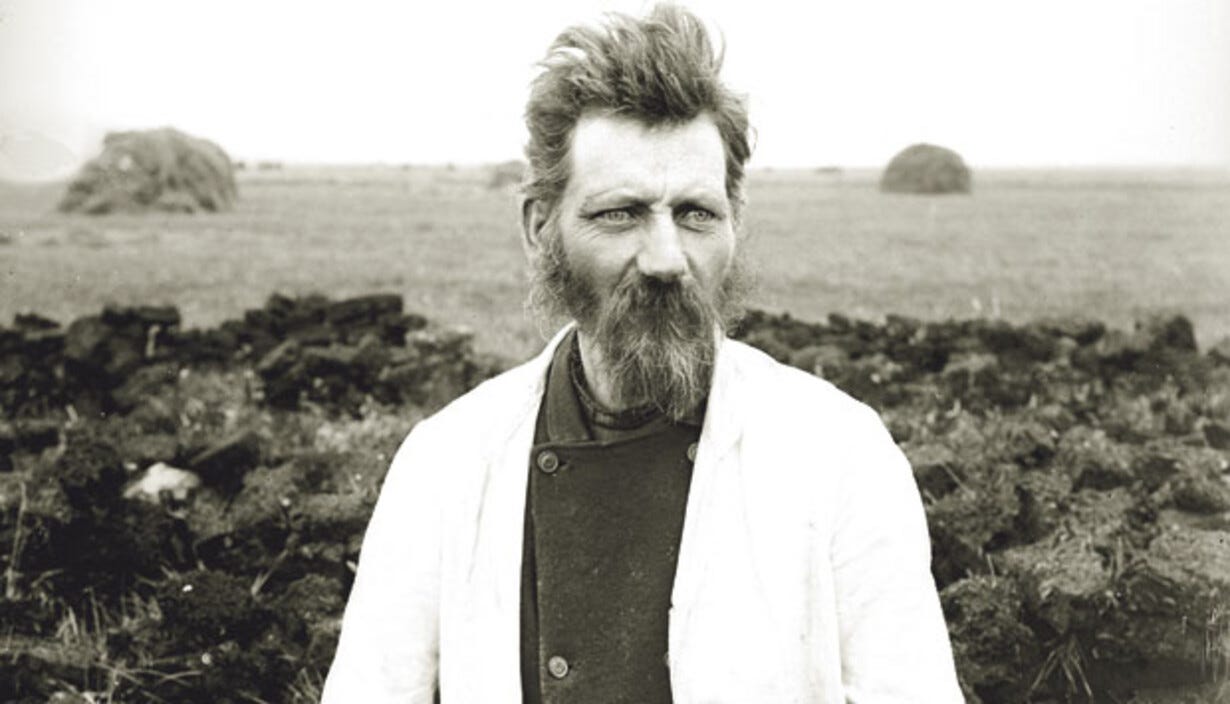

Danish folklore collectors in the 19th century often worked with an "11th-hour" mentality, driven by the urgency of preserving fading traditions. As the old ways rapidly disappeared, gathering material for posterity became a now-or-never endeavor. This urgency sometimes led to questionable methods, as illustrated by Kristian Vestergaard’s account of Evald Tang Kristensen’s rather forceful approach to obtaining his material. The two traveled to Tranflod to meet one of Evald's informants, the potter Erik Larsen. When they found he wasn’t home, Evald refused to let that be a setback:

We were visiting a man whose father had been a renowned charlatan. When we arrived, the man wasn’t home, but we asked his wife to check his drawers to see if there was anything of interest to E.T. Kr. She searched through his desk but found nothing noteworthy.

“You know nothing about this,” E.T. Kr. said, pushing her aside. “Let me see for myself.” He then rummaged through the drawers, eventually uncovering a couple of manuscripts, which he took, assuring the wife they had no use for them. I wasn’t sure what they contained, but they looked like handwritten leechbooks or songbooks.

When I met Erik the next day, he was furious about how his wife had been treated and that his papers had been searched. “Oh,” I said, “you know E.T. Kr.—he’s as mad for old manuscripts as a cat is for fresh milk.

The manuscript Tang Kristensen took with him, or stole, was a fragment of a grimoire, which has since been reunited with its other half, discovered after Erik's death. It is likely that Erik’s wife, Marie, deliberately overlooked the book in 1873, as many people were uneasy about owning works on witchcraft.

The magical formulas were written in red runes. Runes had been used in Danish grimoires since 1771, when Søren Rosenlund published his influential Sybrianus. Rosenlund’s idiosyncratic use of runes established the tradition of incorporating runic script into magical texts.

An example of red runes in grimoires can be seen on this page from a Jutlandic leechbook.

It is hereby declared: in the name of Jesus Christ the Nazarene, that all worms that pain and torment this child, devour its flesh and drink its blood, these shall at once disappear. As true as the Virgin Mary was a maiden pure, these worms shall perish at this hour. This shall come to pass, as true as God is almighty and does not belie His word. In the name of God the Father, in the name of God's Son, and in the name of the Holy Ghost. Amen, amen, amen. Albarapaa, albarapaa, albarapaa.1

The idea of worms as agents of disease has deep and widespread roots in Germanic tradition. Charms against worms appear in numerous historical sources, such as the Old Saxon charm Contra Vermes and the Old English charm Nigon Wyrta Galdor.

If you're interested in exploring more Danish folklore, check out my posts: "The Ballad of Thor’s Hammer in 19th-Century Jutland" and "The Wild Hunt for Saggy Long Tits”.

The ballad of Thor's Hammer in 19th century Jutland

The tale of the theft and recovery of Thor's hammer has proven to be remarkably popular among philologists over time. Few other Old Norse poems have been the subject of as much scholarly attention as this particular myth. The story is chiefly known from the Eddic poem

Herved tilsiges: i den herre iesu christi nazaraei navn, at alle de orme, som der piner og plager dette barn, fortaerer dets kiød, og drikker dets blod, disse skal stax forsvinde, ligesaa sandt som iomfru maria var en reen møe, skal disse orme, i denne time døe - det skee saa sandt, som at gud er almaektig, og ikke ly(?)ver sit ord - inavn gudfaders - inavn gud søns - ok inavn gud den helligaands amen. amen amen amen albarapaa - albaarapaa - albarapaa

Where can anyone buy your translation of the “Sybrianus”?